By the time I heard Onanon they’d been broken up for ages.

That didn’t bother me much. They might as well have been The Clean, as far as I was concerned. They may as well have been Black Sabbath or Nina Simone. I lived in Linkwater; every good band was mythical. Even the ones who were still going seemed out of reach and possibly made up. Regardless of their status, regardless of their realness, Onanon sounded the way I wanted music to—they were catchy and chaotic, with perfect guitar leads that gleamed menacingly, and funny, violent songs called things like ‘Strawberry Feel Up’ and ‘Cold Fish’.

How I felt about Onanon was the kind of obsession where you buy the t-shirt and hope someone at Four Square has the same shirt on, and they are attractive, and you fall in love.

When I got out of Linkwater I saw there were folk around who cherished the band in the same way I did. To a certain stranger you could just say it “Onanon” and watch a little rush go through them. An excitable inner yip! And how thrilling(!) to find pockets of Onanon-believers all mixed in with the rest. I’d imagine them dispersing off home to their outwardly modest, spiritually blooming lives: contentedly singing “Normal-Norman in Normanbyyy, I don’t know what’s come over meee!” as they ironed mountains of undies, or pulled browning, half munched apples from their children’s lunchboxes, or scrubbed disobedient dogs clean in the bath.

For all the potent and accumulated glint in the eyes of their acolytes, though, there was bugger all praise for the band in print.

In 2019 I txt Dave Local, head of Dunedin label, Monkey Killer Records (where I’d bought the shirt) saying “Hey, is this the right Dave? Been wanting to write a piece on the brilliant and beguiling group Onanon but don’t know anything about them. Could you do it?” to which he replied (seriously instantly) “I love that band! And I live with the bass player, Karen—so yes!” and then he did do it. He wrote about Onanon – beautifully – and I (as I do) got distracted by bits and pieces (but nothing too substantial) for 2+ years.

Below is Dave’s piece: freed at last from my desktop, and accompanied by pictures.

Thank you, Dave, for this. You are the glue, and I love you!

***

It’s been a good decade since Dunedin lost Onanon, one of its beloved underdog bands that epitomised the scrappy DIY ethos of the local music scene while alternately searing that scene’s ear-ways and tickling its chin. From the turn of the century to 2009, Onanon evolved from amorphous primordial ooze into a potent, at times maniacal, beast. They were best remembered as the scrappy younger sibling to Dunedin’s steadfastly independent gat-rock legacy, epitomised by acts like the 3Ds and High Dependency Unit. When they finally rent themselves asunder they left behind a scattershot legacy of recordings and fondly remembered, sometimes raucous/sometimes messy, live shows.

Onanon were a Dunedin band, one enamoured of the city’s legacy of chaotic noise, lamenting its seeming demise by the end of the nineties. “I knew Glen through Don way before we even did music stuff, so I knew Glen was into that kind of guitar music stuff. And he loved the 3Ds, and we needed to hear something like the 3Ds,” says Karen McLean, Onanon’s bass player, forming the heart of the band with her long-term partner, Donald Ferns, and Don’s old work colleague Glen Ross sometime around 2000. “We were really into HDU and quite sonic stuff as well,” Glen says, while The Clean, Snapper, Bailterspace et al provided the necessary psychological template and anyone-can-do-this impetus to get the nascent ball rolling.

The quartet was completed with the addition of Alan Cameron on drums. “Al was a friend of a friend, he said he was really keen to play drums in a band, but he’d never played drums before” Glen says.

“He had a really interesting way of drumming; he was quite unconventional,” recalls Don. “And Al was in, like, a pipe band?” Karen asks, querying her memory. “And he had never sat down at a drum kit before. And he had the principle, he had rhythm and that’s all that really mattered.”

“It was all pretty organic, but inevitable,” agrees Don.

Semi-formless jamming eventually turned more serious. “It was pretty much just instrumental for six months or a year; we didn’t have any songs. We’d fucked around a lot and thought, ‘Let’s just write some songs, some actual pop songs, instead of being instrumental,’” elaborates Glen.

“Glen might bring along Tapeworm or Uri Gellar [sic], but we would only get a skeleton; they were only riffs. So we would get a skeleton, but the difference between the demo and what we ended up with — might be ours would have three arms and one leg,” Karen adds. “We didn’t have any aims, we didn’t want to play live, we weren’t really interested and then we liked the songs and went, ‘Aw, shit man, maybe we should see whether other people like them.’”

Early shows were relatively informal, and Glen’s song-writing proclivities combined with not-insignificant contributions from Karen and Don gained them plenty of encouragement from Dunedin’s ever-present noise scene, playing such ‘illustrious’ venues as The Gresham, The Crown and ARC Café.

“We did get a lot of positive response from people in the community,” Don recalls.

With a somewhat ramshackle noise-pop sound and the joy of musical creativity burrowing further into their brains, Onanon turned to smearing their creation onto tape. “It wouldn’t have occurred to us to get someone else to do it; you just recorded it at home and packaged it yourself. That was how you did it. Those were the rules. The Clean were a good example: Bob Scott’s handwriting was on the covers. They’d do their own artwork. And Chris Knox is the ultimate master of all that stuff. That was the cultural mana we were coming from. We wanted to have some sort of visual expression of what we were making. We all liked KFC — that was the reason for the Quarterpack EP,” says Don.

“I really wanted grease. I wanted it to be representative of a certain fried chicken chain. Don mocked up a really good one and I was like, ‘Nah man, not greasy enough,’” Karen adds.

Released in 2002, the Quarterpack EP had been a DIY labour of love from start to finish: composing the music, recording at home, creating the artwork, printing the covers at home, endlessly burning CDs and distributing them all themselves. Showcasing songs from the three songwriters in the band, there were hints to where things would go with proto-classics like Don’s plaintive Don’t Let a Good Thing Go, and Karen’s open-spaced instrumental Peninsula taking pride of place with the early version of Glen’s potential screamer Uri Gellar. Overall it was an interesting slice of the emerging band at the time: loose, skittery and with a submerged melodic heart overlaid in noise.

After becoming well entrenched amongst the like-minded Dunedin musical collective and receiving support from the likes of the local student radio station, Radio One, 2004 saw drummer Al upping sticks and leaving. “Al went to Auckland; he’s quite academic and he’s lecturing. He went on to a normal life. There’s a veneer of normalness, but underneath he’s one of us,” recalls Don, fondly. A final show with Al (supporting Trans Am on the Dunedin date of their New Zealand tour) gave way to searching for a replacement and a way to carry on. Enter Anthony Anema (better known as Ants) who was introduced to the band by mutual friend Scott Muir.

“I said I wanted to get into a band in Dunedin because I was playing in a few in Rotorua,” says Ants, after he and his partner moved south. Although musically things gelled pretty much straight away, there was a feeling-out period for the various personalities. “I wouldn’t say we clicked straight away,” says Ants, “I always thought they were really straight as, because they looked like squares. I think it was the glasses. We had a really good jam, though.”

With the feeling-out period over and Ants firmly planted behind the drums, Onanon transformed into an altogether more muscular beast. “Ants had really good geometry to his playing. Al was very organic; Ants was very organic plus precision,” states Karen.

The previous couple of years had seen Onanon strike up another fruitful collaboration: they met Thomas Bell when he was still part of the ARC café and record collective and found a kinship they would foster until the end of the band. When talk turned to more recording, they settled on the recently re-opened Albany Street studios with Thomas, committing to magnetic tape the bulk of the debut album Hang On, I’m Still Mutating over a single weekend in December 2003.

“That room was brilliant! It was fun, and there were corridors, and it was all very The Shining,” Karen laughs. And the kinship with Thomas Bell was formed instantly too. “Tom was our George Martin. He was on our wavelength.”

“We grew with him a bit,” adds Don, “We had a great time in there recording with Tom; we felt like the fucking Beatles.”

While the DIY ethos of the album carried on through the album artwork, this time it was released as a properly pressed CD with nary a CD burner in sight. The front cover and inner sleeve (featuring Otago Harbour) were pictures taken around their homes, though. “The centre-fold was Ants’ view, so it represented going up to practice at his place,” Karen elaborates.

Released in 2004, Hang On, I’m Still Mutating was a stellar leap ahead in sound quality and garnered Onanon attention slightly further afield than the insular Dunedin music community. But it still featured some songs roughly recorded in the lounge at Macandrew Bay and (most memorably) a bonus track about Charles Manson recorded to Don and Karen’s answering machine by an excitable (and most likely drunk) Glen one night.

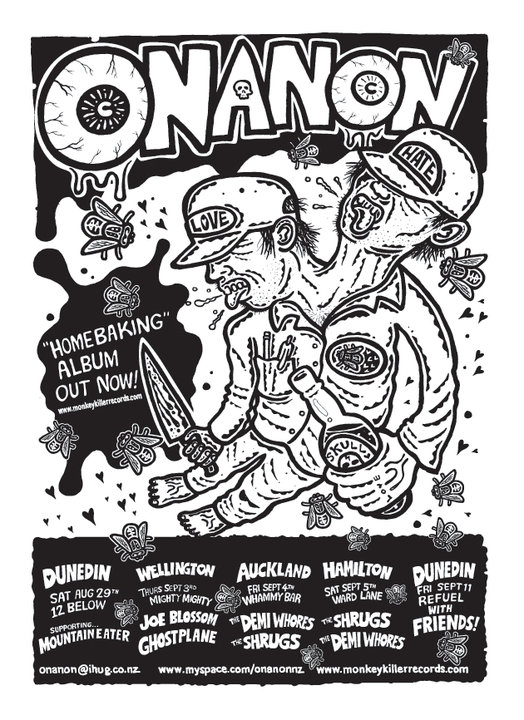

The album saw A Low Hum and Powertool Records taking an interest in the band, seeing the debut distributed to New Zealand record shops and the band play notable events such as Camp A Low Hum. After recording another EP titled Sneepy at Thomas Bell’s studio in 2004 and 2005 (released 2006), and making a semi-professional video with established editor Chris Tegg for the song Bugged (“God, that drove us up the wall, that one,” Karen says. “Twelve hours of playing the song over and over”), the band got to work on what would become their penultimate statement, Home Baking.

So named for the packages Don would receive from his Mum, the album artwork included beautiful depictions of homely treats, along with recipes for some. “We were fuelling ourselves on Don’s Mum’s shortbread,” states Karen. “Even though he was a grown adult man she kept sending him food. You’d open it and it would all be wrapped in tinfoil like contraband.”

The bulk of the songs were penned by an increasingly prolific Glen, with the typical themes of weirdness, madness and death wrapped in digestible bites of blackened pop. “There’s a lot of black humour in those songs. Dark lyrics over happy tunes,” says Ants.

“I love happy, melodic shit, and a dark undercurrent with it,” agrees Glen. “I like my songs to be based around something real, something that actually happened. Seacliff was based around my Aunty Myrtle who worked at Seacliff, and Fluffy White Clouds was about a guy that I went to school with who ended up killing his wife and tried to kill his two children and then set himself on fire. So there were lots of experiences to draw from, really.”

By the time Home Baking was ready for release in late 2008, Don and Karen’s relationship was facing severe pressure, fuelling the intensity of not only the Dunedin release show, but also the New Zealand tour that they had committed themselves to.

“I remember there were lots of terrible personal things happening, that night,” Karen reflects, “but the music itself was really good, and we were really happy with the sound of it.”

“Don particularly had an energy about him around that time, “ recalls Glen.

“There was a lot of anger in there,” adds Ants.

“I remember the Home Baking release and man, Don was attacking his guitar, torturing it,” says Glen. “It sounded fucking great. I could tell he was in some pain as well, man; it was pretty a horrible time for him I think.”

“I’d been keeping a lot under my hat at that point,” adds Don. “I wasn’t really happy, and playing the music was a big release for me. A lot of the songs were break-up songs, like Glen’s songs were break-up songs with Kobe, [and] at that time Karen and I were going through a break-up, so it was almost like that music became me, or us, or something. Throughout all that the music was a great release. It was my favourite thing to do.”

The Dunedin album release show was followed by shows around the country, where five years of playing together and the tension around their personal circumstances fuelled an extra cathartic bevy of performances.

“The music was great,” states Ants, simply. “That tour in particular we just slayed it.”

“That was a great tour,” concurs Glen, “and hats off to Don and Karen; they stayed professional during the whole thing. We were traveling pretty tight.”

Before they departed for their final tour, the writing was on the wall for the demise of the band.

“We could have kept on going; it was just too hard,” says Glen. Karen and Don broke up, but the band itself still had unfinished business. Their final batch of songs were recorded during Waitangi weekend of 2009 in Port Chalmers for the Bad Vibrations EP, with Don finally letting his personal anger out in song and Karen’s resignation to the situation made plain amongst Glen’s likable death-ditties.

Karen explains: “I’m glad we didn’t try to push more recording after that. We were mining too deep. We were starting to run out of examples in our lives to use in our music and we were starting to hit some heavy shit, about parents and death and stuff. So, time to take a break. Or, just stop.” Ants felt differently though.

“It didn’t feel like it had been exhausted. I was still really enjoying playing, that’s for sure,” he says.

But it had to end, and Onanon played their final show, a free entry affair at Dunedin’s underground cavern Re:Fuel in March of 2009. With a mixture of personal anger, resignation and just a mere hint of regret that it had to end this way, Onanon’s end was catharsis mixed with blithe disregard. If they have a legacy, hopefully it is of finding the joy in a blissfully dark belligerence.

“It’s anger and aggression and stuff, but in a positive way,” Don summarises. “With Onanon, it seemed the darker the material, the happier the response of the people who were into it.”

Karen’s summary of Onanon’s time is equally as succinct. “Play until it stops being fun. And it was fun for a very long time.”

Dave Local, 2019

Left to right: Donald Ferns, Karen McLean, Anthony “Ants” Anema and Glen Ross.

One thought on “More Grease! An Onanon Story.”